Is letting a stranger into our house through Airbnb inherently safer than picking up a stranger from the kerbside, or has there simply not been a horror film about the sharing economy yet?

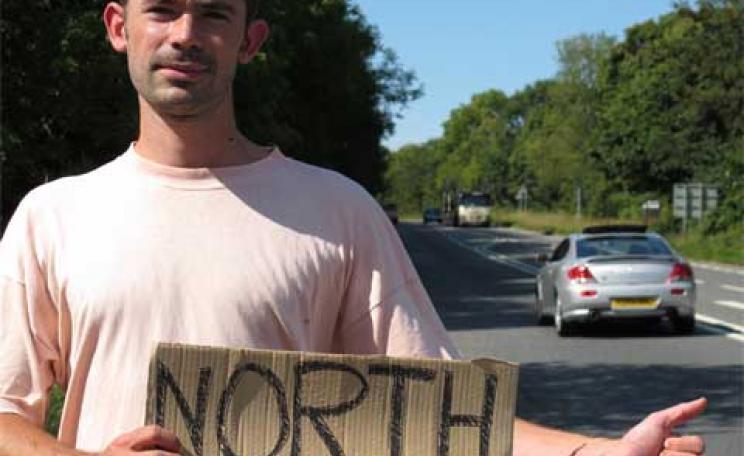

Last month I hitched 400 miles from Glasgow to London, an eight hour drive that took me twelve. I had read a review that The Land had published of Beyond Flying, a book to which I had contributed, that explores alternatives to aviation.

"Sadly", Simon Fairlie wrote, "the book fails to mention the only motorised form of transport that entails no carbon emissions and is the most challenging and rewarding of all, namely hitch-hiking. It is missing because nobody hitchhikes any longer."

I hitch-hike, I thought. I have hitch-hiked for half a lifetime since I first stuck out my thumb on Long Island at the age of 16 and a Cadillac with its top down pulled to a stop five minutes later.

Aftter thousands of miles on four continents, despite being able to afford the train these days, and although Megabus could get me there for ten quid, I've never got sick of it.

"The sudden disappearance of the hitch-hiker in the Thatcher years is a sociological mystery that remains unexplored", the review continued. It felt like something worth exploring.

The Glasgow to London route is one I have taken many times. I have my spots I like to stand, the roads I know I must avoid, my favourite service stations. I have been picked up by bands on tour, by truckers, by soldiers, by canoe instructors and canal boat enthusiasts and by plenty of travelling salesmen.

I have squeezed in amongst families and I have kept lone drivers company and I have tried to act calm and cool as two mechanics felt the need to show me that their car could reach 160mph. I have heard stories of the most personal nature, of family breakdowns and of secret love, and once I was dropped at my front door. I have never bumped into another hitcher.

It is voyeuristic, educational, tedious, addictive. It feels like a relic of a bygone age and it feels revolutionary. I know of few forms of transport that give you that, few forms of transport that feel like accomplishment upon arrival, and all without costing you a penny.

"Until human nature changes for the worse", Chapman Milling wrote in 1938, "rides are going to be given to decent-looking people who ask for them."

And still they stop

There is widespread belief that no one stops anymore. I have been told it by car drivers who have picked me up ("none of the other bastards will stop for you"), told it by former hitchers who believe that the world has moved on, and told it by the media.

When the Automobile Association, in 2011, announced that 91% of drivers would not pull over for a hitcher, the headline writers seized upon it. The end of the road for hitchhiking, they said. Thumbs down for hitchhiking. That one in ten drivers consider stopping is actually fantastic odds.

Is letting a stranger into our house through Airbnb inherently safer than picking up a stranger from the kerbside, or has there simply not been a horror film about the sharing economy yet?

Only one percent of drivers, the survey continued, said that they would definitely stop. The game lies in that eight percent, the undecided, who really believe they might stop when answering a survey, but who need a bit more convincing when confronted by an actual situation.

"The signal, which includes the whole movement of the body", writes Georges Limbour in La Chasse au Merou, "is so vital that you can say it's as often the hitch-hiker who picks the driver up as the other way about." Like fishing, you choose your spot. You employ everything that you know about the habits of what you want to catch, and then you leave the rest up to chance.

The term 'hitch-hiker' blew in from across the Atlantic and arrived here in the 1930s, though there were people flagging down wagons and lorries long before there was a word for it. During two weeks of a General Strike in 1926 the culture momentarily flared, and when it ebbed again the Daily Herald was moved to write:

"Civilisation must, if it has any reality, any value, make us ready to give anyone a lift in any way possible, not only at moments of crisis, but in ordinary humdrum times."

But it took another crisis, the Second World War, for hitching to truly become commonplace. Servicemen hitched home on leave, parents visited their evacuated children and commuters thumbed to work five times a week. It was part of the war effort, sanctioned by the Ministry of Transport. But as with the General Strike, goodwill faded along with the Fascist threat.

"In November 1945", recounts Mario Rinvolucri, "an airman hopefully thumbed a large Buick saloon - the driver cowed down and shouted through the window: 'Don't you chaps realise the war is over?'."

Fear of the stranger

The post-war boom created a new sort of hitcher. "Nothing behind me, everything ahead of me", Kerouac wrote, "as is ever so on the road", and with his writing stuffed into a backpack, the next generation thumbed their way into a Europe still torn by the war, but suddenly without boundary.

The coming decades were fuelled on the twin benefits hitching provided, travel on a shoestring and guaranteed adventure. The road is a ripe candidate for metaphor, and a form of travel upon it that defied order and regulation was particularly potent.

Since then it has been downhill. There is still the occasional pocket in some remote parts of Britain where the public transport is creaking or non-existent, but they are few. I often feel like a relic, as likely to get photographed as to get picked up.

The reasons given for the decline are predictable enough: the rise in cheap cars, the gap year and the budget flight, the stigmatisation that the stranger has undergone. The stranger is a wild and uncertain concept, and hitch-hiking, when two strangers are placed in an enclosed and intimate space, is a particularly good situation to gauge current attitudes towards them.

Fear of the stranger, the paedophile or the terrorist has grown pervasive, while the slasher films of the 80s, targeted Public Service Announcements, and media focus upon the occasional tragedy have all contributed to demonising hitchhiking.

And yet despite all that, I always get a ride. There is no shortage of those that once hitched who are looking to return the favour. Many are eager to invite me in and relive something of their youth, to hold up the other end of a bargain they made when they were hitching forty years ago.

If there is a decline in trust, a rising fear, then it is most prevalent in my generation, in the hitchers. The AA survey bears this out. It is the 18-24 year olds who are least likely to have hitchhiked, followed by the 25-34 year olds. It is us who have grown up in a society more ordered and controlled than any that has gone before.

Maybe we like our travel more predictable, our strangers kept at arm's length. With rising petrol prices and record youth unemployment, along with a need to cut carbon emissions, I have long thought it time for a renaissance, but hitch-hiking steadfastly refuses to make a comeback.

Clicking a ride

But whilst some of us sit about pining for hitching's heyday, BlaBlaCar, the leading car share website in Europe, has been gathering 10 million users. Last month they secured another $100 million of funding. Drivers post their journeys, passengers search for journeys and contribute to the petrol costs.

A million journeys are made every month, from which BlaBlaCar pockets €2 per ride. It's not possible to offer a journey for free. Along with many other websites and apps now proliferating across every continent, it's being called 'digital hitch-hiking'.

The sharing economy is hip right now. Airbnb, Zipcar, Taskrabbit, Poshmark, the internet is awash. Sharing bikes, sharing rooms, sharing skills, sharing cars, sharing, as the New York Times has reported, illegal handguns.

The industry is valued at £15 billion, much of it little more than platforms that allow users to rent out and cash in on the excess in their lives. Their manifestos buzz with words like 'community' and 'trust', of cutting out the middle man.

"It's like the UN at every kitchen table", said Brian Chesky, Airbnb's CEO. But as his company floats on the stock market and Zipcar is bought by Avis, it becomes harder to suspend disbelief that this is not just capitalism dressed up, once again, in sheeps' clothing.

Breathless editorials speculate that the sharing economy has the power to do anything from liberating workers from the nine-to-five bind, to creating a slow-burning revolution that could overthrow the current economic system.

But it could also be seen as the free market par excellence, as we work 24/7 with no contracts or safety nets, branding ourselves in order to market every aspect of our lives, whilst the companies that provide the platforms sit back and rake in the billions. Wasn't hitch-hiking better than that?

Going digital, London to Bristol

I tried hitch-hiking digitally for this piece. I thought I should. I was feeling somewhat curmudgeonly, like I was longing for the days of steam. I found a ride for £9 from London to Bristol. A train would have cost me £42. Even getting the tube out of London far enough to stick a thumb out would have been more than a fiver.

I waited in a car park in Stratford and a woman turned up and took me where I wanted to go, to arrive at the time we had agreed upon. Money changed hands, few words were spoken. Did I feel the same thrill of adventure? No, I manifestly did not. I felt like a consumer paying for a commodity.

If my arguments for hitch-hiking are environmental, social, economic, perhaps even anti-capitalist, then such transactions make good sense. Not only does a car get taken off the roads, the structured nature of the trip opens it up to those who do not have the time or inclination to wait for hours by the roadside in the rain, which, let's face it, is almost everyone.

Last year 61% of car journeys in the UK had just one occupant, and this is one step to reducing that.

I once wrote an article for The Ecologist making the case for a resurgence in hitchhiking couched in environmental arguments, but I conveniently ignored this boom in car shares to make a case for something which, I realise now, I felt sad about on a more personal, poignant level.

If it's about adventure, well that seems like it's no one's concern but mine. And yet, as I looked out at the M4 rolling past, I realised that, for some reason, I still didn't feel quite ready to let it go.

HitchBOT or Hitchcock?

Over the course of three weeks this past summer a robot named HitchBOT, standing the height of a six year old child, thumbed its way 3,500 miles from Halifax to Vancouver. Frauke Zeller, one of its creators, speaks like a concerned but loving parent of letting their offspring fly the nest.

They left it at the roadside outside Halifax Airport, followed the updates it posted on Twitter, and went to meet it three weeks later on the other side of the country. "We said well, we give it freely. We couldn't do anything really. We never once thought about stopping the experiment. All we wanted to see was it arrive safe and sound in Victoria."

HitchBOT is made from a beer cooler and has rubber gloves for hands. Speech recognition software and a link to Wikipedia allow it to keep up a conversation. There are pictures on Instagram of drivers taking it camping, to weddings, to football games.

When Zeller met up with it in Vancouver at the end of its journey she described it as looking a little like a shuttle after re-entry, its speech somewhat garbled, but being otherwise unharmed. I have returned home in a similar state after several weeks on the road.

The experiment was conceived as a way of exploring whether robots can trust humans, and hitch-hiking seemed an appropriately vulnerable situation for their creation to enter into.

"The cultural perceptions, notions like security and safety, all that is very closely connected to the discourses around robots. That's why we thought it might be interesting to bring those areas together.

"When we had the welcome party in Victoria we met someone who had just hitchhiked across Canada who was just a couple of days behind HitchBOT. He got at least five rides from people telling him that they only stopped because of HitchBOT. Before HitchBOT they would never take hitchhikers with them."

We can only suppose how this human hitch-hiker must have felt. Probably grateful. But also perplexed that a three foot high machine with a smiley face, cobbled together with junk from a dime store, had cleared the way before him of cultural stereotypes many years in the making.

That a robot was able to change attitudes in five people is heartening, if not irrational. The ways that we choose to trust, or not, are curious: because some money has changed hands, or a profile on the internet, or a good experience with a robot.

Is letting a stranger into our house through Airbnb inherently safer than picking up a stranger from the kerbside, or has there simply not been a horror film about the sharing economy yet?

When the journey is the destination

Maybe I grew up reading too much Kerouac, and maybe I'm getting old. But I do think that there is something important about hitching that the carshare websites miss. At its heart it is an exercise in trust, of challenging what we thought we knew about people.

Putting ourselves in a position of vulnerability and seeing what happens; those unplanned interactions between strangers where anything is possible. I am writing this as a man in my thirties, and I realise that other people will have their own approaches to risk. But there seems to me benefit in making our own choices, learning for ourselves, rather than outsourcing them to a company and paying for the privilege.

Hospitality does entail risk, but it is no less worthwhile for that. By subjecting it to the treatment of screening and profiling, by attempting to eliminate that risk, we end up by eliminating the hospitality itself.

Being able to rely on strangers, on communities, on trust, are values that are worth preserving, and if we destroy them we are perversely destroying things that can truly keep us safe. As one driver put it: "I wouldn't pick up hitch-hikers either. I'm not nuts. I do that to protect myself. But protecting myself has no value to society."

I worry for hitch-hiking's future. If we don't hitch then the next generation of hitchers will have no one looking to return the favour.

If 'sharing economy' websites continue to thrive then we may come to the idea that any bit of kindness that we might once have offered has monetary value. It will still be easy to get from A to B. Travel will become cheaper, more environmentally friendly.

But I will arrive in B exactly the same person as when I set out from A, and it's worth remembering, sometimes, standing by the side of the road with a hopeful thumb out, that it could be about more than that.

This article was originally published by The Land magazine Issue 17, Winter 2014 / 2015. See the original article.