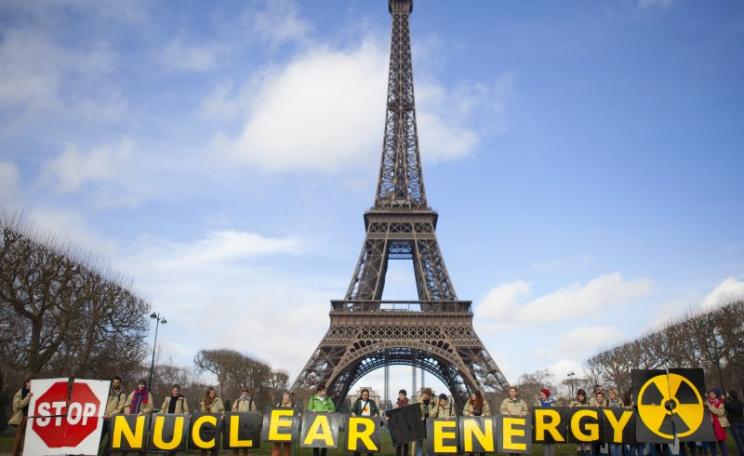

Clarity on legal aspects and signs of convergence on contentious issues need to materialise as early as possible to ensure success in Paris. With only six months left, the pressure is on.

The countdown to Paris has begun.

At the February talks in Geneva, governments agreed the basis for the negotiations that will follow in Paris this December.

The 90-page official negotiating text covers the substantive content of what will form the new climate change agreement, including mitigation, adaptation, finance, technology and capacity building.

The text contains, however, an array of varying proposals and options for addressing these elements. The section on adaptation for example, presents as many as 13 alternative wordings - of which only one can go forward into the treaty.

Climate negotiators are meeting again in Bonn next Monday, 1st June and their task for this ten-day meeting is big. They are expected to commence a lengthy and granular process of narrowing down the text, negotiating line-by-line and trying to find common ground.

While some textual options present marginal differences, some others suggest radically opposed views. Take the issue of finance for example, and the cross-cutting issue of 'differentiation' - as in the "common but differentiated responsibilities" principle of the Climate Convention.

Even now, the legal status of any treaty remains uncertain

As COP 21 in Paris moves closer, attention to the legal form of the new agreement needs to intensify swiftly. This is an aspect that as been barely covered so far.

Apart from setting out that the new agreement could be "a protocol, another legal instrument or an agreed outcome with legal force", as set out in the Durban mandate, there has been no further specification as to what is intended or covered by each of these options.

There is, of course, room for interpretation in respect of the implications of each of these potential outcomes. But when thinking about these options it is important to consider that the legal form of the agreement alone does not determine its strength or legal force.

In other words, legal 'bindingness' does not only depend on form, but also on the wording deployed in specific provisions and whether these create rights and obligations on States. For instance, even if the new agreement takes the form of a legally binding Protocol, this does not mean that all provisions will be clearly enforceable.

Provisions can always be formulated in generic terms, or refer to general aspirations, commending Parties to increase efforts without creating legal obligations as such. Such is the case with phrases such as 'as appropriate,' 'if necessary,' 'insofar as possible,' and 'all practicable steps' (see UNFCCC Article 4.5, for example).

However provisions spelled out in rather mandatory language, e.g 'shall', 'must' can envisage specific activities and set out binding and clearly enforceable commitments. For the Paris agreement, language is thus fundamental.

Clarity on legal aspects and signs of convergence on contentious issues need to materialise as early as possible to ensure success in Paris. With only six months left, the pressure is on.

The Durban mandate is also silent in respect of the structure of the new agreement - specifically, whether the Paris outcome should comprise only one instrument or consist of multiple instruments.

Many Parties support the view of a mixed outcome or 'package', comprised by a 'core' agreement (taking the form of a Protocol) and supplemented by implementing documents such as COP decisions.

Under this form, however, it is unclear what may be included in the core agreement and what may not. Key to this are the so-called INDCs or 'Intended Nationally Determined Contributions' which lie at heart of the process.

These are the public statements made by countries which set out the post-2020 climate actions they intend to take under a new international agreement - and as such, they will largely determine the nature and scope of any treaty agreed in Paris.

But there is no uniform opinion as to whether the INDCs should be inscribed in the core agreement, for instance as an Annex, Appendix, Attachment or Schedules; or elsewhere, for example as Convention of the Parties (COP) decisions - which are not legally binding on states.

Similarly, where to place issues like loss and damage - critical issues for some of the most vulnerable countries - is also important. If they are incorporated as COP decisions their status will be greatly weakened. But if they are enshrined in the agreement itself, that would formally enhance its status.

Commitments contained in this legal form stand a better chance of compliance - providing of course that obligations are clearly defined and spelled out in mandatory as opposed to aspirational form, as outlined above.

Key issues remain unresolved - and time is short!

So, if a 2015 Package is agreed in Paris, a key issue for parties would be to distinguish issues of particular importance, hence integrated into the core agreement with stringency and more detail, and other matters that can be addressed in more general terms in complementary documents.

Like the issue of legal form and structure, another fundamental question ahead of Paris relates to how the burden of mitigation will be shared between developed and developing nations in the new agreement.

While the Kyoto Protocol establishes emission limitations and reduction targets for developed countries only, in the realm of the current negotiations 'all Parties' are expected to make contributions, however, as set out in Lima, this wil be "in light of different national circumstances".

While this indicates a move away from the traditional distinction between developed country parties (listed in Annex I of the UNFCCC) and all others, nothing on the matter of differentiation has been settled yet. With some countries still supporting the existing form of distinction, polarized views prevail on this matter.

The Geneva negotiating text keeps the show on the road towards a new climate deal by 2015. However, countries need to make the most of the ten days of negotiations available to them in June - which, in the face of the challenge, is looking like a very short time indeed.

Clarity on legal aspects and signs of convergence on contentious issues like differentiation need to materialise as early as possible in order to ensure success in Paris. With only six months left, the pressure is on.

Illari Aragon is Programme and Outreach Officer for the

Legal Response Initiative (LRI).

More information: The Legal Response Initiative (LRI) supports developing nations at the climate change negotiations. LRI runs an advisory service in real time, produces briefing papers and implements training for country delegations.

LRI is supported by the Climate and Development Knowledge Network (CDKN), which aims to help decision-makers in developing countries design and deliver climate compatible development.