they evolved incredibly potent and efficient venom, three to five times stronger than any mainland snake's - capable of killing most prey and melting human flesh almost instantly.

From Iguazu Falls to Lençóis Maranhenses National Park, there are some breathtakingly beautiful places in Brazil.

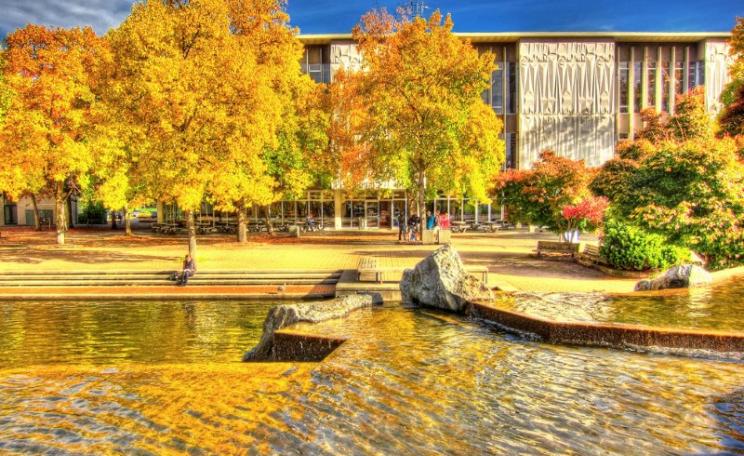

Ilha da Queimada Grande, located about 90 miles off the São Paulo coast, seems like another one of those beautiful places - at first glance.

Almost every Brazilian knows about the island, but most would never dream of going there - it's infested with between 2,000 and 4,000 golden lancehead vipers, one of the deadliest snakes in the entire world.

These vipers' venom can kill a person in under an hour, and numerous local legends tell of the horrible fates that awaited those who wandered onto the shores of 'Snake Island'.

Fishermen's tales

Rumor has it a hapless fisherman landed onto the island in search of bananas-only to be discovered days later in his boat, dead in a pool of blood, with snake bites on his body.

From 1909 to the 1920s, a few people did live on the island, in order to run its lighthouse. But according to another local tale, the last lighthouse keeper, along with his entire family, died when a cadre of snakes slithered into his home through the windows.

Although some claim the snakes were put on the island by pirates hoping to protect their gold, in reality, the island's dense population of snakes evolved over thousands of years - without human intervention.

Cut off by rising seas at the end of the last ice age

Around 11,000 years ago, sea levels rose enough to isolate Ilha da Queimada Grande from mainland Brazil, causing the species of snakes that lived on the island - thought to most likely be jararaca snakes - to evolve on a different path than their mainland brethren.

The snakes that ended up stranded on Ilha da Queimada Grande had no ground level predators, allowing them to reproduce rapidly. Their only challenge: they also had no ground level prey. To find food, the snakes slithered upward, preying on migratory birds that visit the island seasonally during long flights.

Often, snakes stalk their prey, bite and wait for the venom to do its work before tracking the prey down again. But the golden lancehead vipers can't track the birds they bite - so instead they evolved incredibly potent and efficient venom, three to five times stronger than any mainland snake's - capable of killing most prey (and melting human flesh) almost instantly.

Visits are strictly controlled

Because of the danger, the Brazilian government strictly controls visits to Ilha da Queimada Grande. Even without a government ban, though, Ilha da Queimada Grande probably wouldn't be a top tourist destination: the snakes on the island exist in such a high concentration that some estimates claim that there's one snake for every square meter in some spots.

they evolved incredibly potent and efficient venom, three to five times stronger than any mainland snake's - capable of killing most prey and melting human flesh almost instantly.

A bite from a golden lancehead carries a 7% chance of death, and even with treatment, victims still have have a 3% chance of dying. The snake's venom can cause kidney failure, necrosis of muscular tissue, brain hemorrhaging and intestinal bleeding.

The Brazilian government requires that a doctor be present on any legally sanctioned visits, in the event of an unfortunate run-in with the island's native population. The Brazilian navy does make an annual stop on the island for maintenance of the lighthouse, which, since the 1920s, has been automated.

The island is also an important laboratory for biologists and researchers, who are granted special permission to visit the island in order to study the golden lanceheads.

Ninety percent of snake bites in Brazil come from lancehead snakes, a close cousin of the golden lancehead. (Both are members of the Bothrop genus.)

Biologists hope that by better understanding the golden lancehead and its evolution they can better understand the Bothrop genus as a whole-and more effectively treat the numerous snake-related accidents that occur throughout Brazil.

Medical potential for the venom

Some scientists also think that snake venom could be a useful tool in pharmaceuticals. In an interview with Vice, Marcelo Duarte, a scientist with the Brazilian Butantan Institute, which studies venomous reptiles for pharmaceutical purposes, described the medical potential of the golden lancehead.

"We are just scratching this universe of possibilities of venoms", he said, explaining that the golden lancehead's venom has already shown promise in helping with heart disease, circulation and blood clots. Snake venom from other species has also shown potential as an anti-cancer drug.

Because of black market demand by scientists and animal collectors, wildlife smugglers, known as biopirates, have been known to visit Ilha da Queimada Grande, too. They trap the snakes and sell them through illegal channels - a single golden lancehead can go for anywhere from $10,000 to $30,000.

Habitat degradation (from removal of vegetation by the Brazilian navy) and disease have also damaged the island's population, which has dwindled by nearly 50% in the last 15 years, by some estimates.

The snake is currently listed as critically endangered on the International Union for Conservation of Nature's Red List. While that might make Snake Island slightly less terrifying for humans, it's not a great deal for the snakes.

Natasha Geiling is an online reporter for Smithsonian magazine.

This article was originally published by Smithsonian magazine.