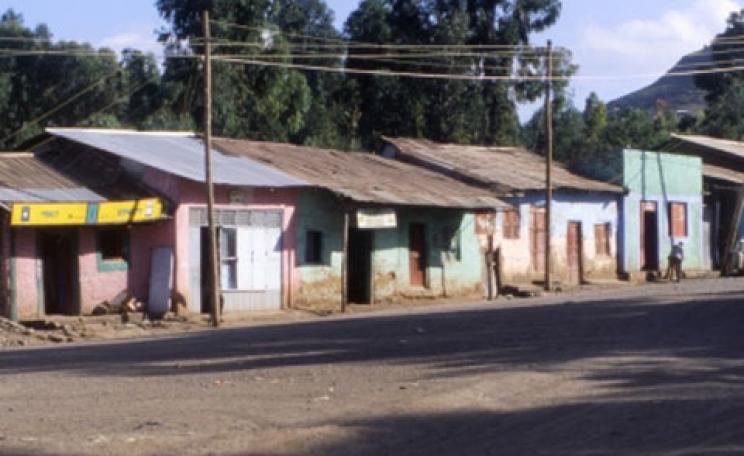

Photograph: Lori Pottinger/International Rivers

Since the dawn of time, history has evidenced that the greatest civilisations were born on the fertile banks of ancient river systems, ranging from Mesopotamia’s Tigris and Euphrates to Egypt’s Nile, China’s Hwang or Yellow river, and the Elvis or king of rivers, the Indus.

Yet the rise of these scientific, commercial and economic powerhouses has not only resulted in technologies seeking to harness the power of rivers as an economic force for good, but also exclusively to dominate this vital source of life through centralised control.

Nowhere is the game of hydropolitical poker so lethal and receptive to drought, conflict and corruption as in Africa, a continent punctured by poverty, mal- and underdevelopment, unsustainable resource exploitation, capital flight, structural adjustment and, increasingly, climate change.

Presently, more than 60 per cent of Africa is dependent on mega-dams as a source of hydroelectric power, such as Zambia (96 per cent), Uganda (99 per cent), Mozambique (91 per cent), Ethiopia (89 per cent) and the Democratic Republic of Congo (99 per cent), in conjunction with a host of client states including South Africa, Zimbabwe, Togo and Benin. This is mainly because, in Africa, water is a shared affair, with waterways composing at least 40 per cent of regional borders.

Intensified drought (increasingly attributed to climate change) has ensured that Africa’s dependence on hydropower simultaneously exports blackouts and energy shortages to countries such Togo and Benin, both crippled by Uganda’s drought. Since 2007, drought has gripped the continent from the east to the south, bringing chaos in its wake.

Currently, Africa supplies five per cent of global electrification, and hosts more than 500 million people who survive solely on biomass, sunlight, paraffin and candles.

‘Most of the Nile states are dangerously dependent on hydropower, including Burundi, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, Sudan, Tanzania, and Uganda,’ says Lori Pottinger, head of southern African programmes at International Rivers. ‘When a serious drought strikes, a hydro-dependent country also has to cope with water shortages and reduced agricultural production.’

And drought is certainly on the cards: geologists predict a 10-20 per cent decline in rainfall over the next 50 years, estimating that 75 per cent of African countries with an annual rainfall of 400-1,000mm are partially located in environmentally unstable zones. The UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has declared Africa ‘the continent most vulnerable to the impacts of projected climate change’ described by South African geologist Maarten de Wit as ‘[like] erasing large sections of the rivers from the map’.

Despite the fact that drought – a climatic reality throughout much of Africa – will be severely affected by altered hydrological cycles, development experts at the World Bank have declared that Africa is underdammed. The World Bank’s energy specialist, Reynold Duncan, recently urged Africa to consider ‘riskier’ assets such as hydropower, stating that just fi ve per cent of the continent’s hydroelectric potential has been explored.

‘In Zambia, we have the potential of 6,000 megawatts (MW), in Angola we have 6,000MW and about 12,000MW in Mozambique – we have a lot of megawatts down here before we even go up to the Congo,’ he said. DRC’s Grand Inga, the world’s largest proposed hydropower scheme, is estimated to possess 40,000MW capacity – enough to power the continent.

This move – promoting mega-dams as development – is backed by development and commercial banks, foreign governments, African initiatives such as the New Partnership for African Development (NEPAD), presently motivating for 13 dam-projects, and resourcehungry ‘middle kingdoms’ such as China.

The power that disempowers

Though Africa already houses more than 1,270 dams, the benefi ts have yet to positively impact on the majority. Mozambique, lauded as a success model, generates enough electricity to power the country, but less than nine per cent of Mozambicans have access to electricity. The bulk of the country’s 2,072MW is exported to neighbouring regions and utilities – such as South Africa’s parastatal Eskom – via cost-intensive, high-voltage transmission lines that account for as much

as 50 per cent of total construction costs. The remainder is utilised by domestic corporations such as Mozal, Mozambique’s aluminium smelter, which is operated by BHP Billiton, one of the largest mining concerns in the world.

‘Most often, large dams provide electricity for foreign-owned industries, water for foreign mining companies and irrigation for large-scale farms,’ says Lori Pottinger.‘Distribution lines are the most needed but least cost-effective part of an African grid system. Priority is given to big consumers – cities and industries, over poor households, low density, and rural areas.

‘Long-range, high-voltage transmission lines are meant to connect two end-points, requiring costly substations to reduce the voltage and distribute along the way. These lines end up passing over thousands of villages.’

Mozambique’s Cahora Bassa, proclaimed by a UN report to be ‘the [dam] with the dubious distinction of being the least environmentally acceptable project in Africa’, is also touted by development experts as southern Africa’s largest hydroelectric dam. According to Paulo Muxanga, chairman of the dam’s operating company, Hidroeléctrica de Cahora Bassa, the dam’s limit has been reached; no additional energy is available for export.

This lack of available hydroelectric power now threatens the energy security of South Africa (the Climate Change Policy Framework 2009 had proposed the use of importedhydropower as a solution to South Africa’s energy shortages). To counter this, NEPAD and Eskom have joined forces in an attempt to fast-track construction of the China-backed Mphanda Nkuwa dam. The selected site is on the Zambezi, in Mozambique’s Tete Province, just 70km downstream of Cahora Bassa.

The 1,600-mile Zambezi is the fourthlongest river in Africa, with the fourth-largest flood plain and a 1,390,000km² basin clogged by 30 dams, including Cahora Bassa and Zambia’s Kariba dam. The latter controls 40 per cent of the run-off.

‘The Kariba dam between Zimbabwe and Zambia was built 50 years ago to power industries in southern Rhodesia and the copper mines of northern Rhodesia,’ says Terri Hathaway of International Rivers. ‘Today, much of their electricity is transmitted 1,700km away to the copper belt.’

The Zambezi supports a population of 40 million people from 30 different ethnic groups. They are dependent on fish harvested in estuaries (the habitat of 80 per cent of the fish-catch globally) and flood-recession agriculture, which has been disrupted by the damming of the river’s natural regime.

Thus far, more than 400,000 people in Africa have been displaced by dams. Globally, 40-80 million have been displaced. During the construction phase of Cahora Bassa, more than 42,000 people were involuntarily resettled, the figure rising to 57,000 for Kariba. More than five decades later, the bulk remain socioeconomically marginalised and lack access to the same electricity that was the pretext – in the name of the greater ‘common’ good – for displacing them in the first place.

Privatising the commons

Selective development appears to be the name of the new Great Game, with ‘neo-colonial’ powers such as China aggressively promoting mega-dams as a means of providing business to Africa-based Chinese corporations in need of power.

In 2006, the Mphanda Nkuwa contract was awarded to Sinohydro, the Chinese corporation behind the Three Gorges dam. The Export- Import Bank of China, the country’s export credit agency (ECA), has guaranteed the project $2.3 billion: $1.1 billion allocated for construction purposes, with $1.2 billion for high-voltage transmission lines.

‘Many of the dams being built by China, such as the Merowe dam in Sudan, are being undertaken to open up doors for China to get lucrative mining contracts, agricultural land, logging rights and other deals,’ says Hathaway.

There is a secret underpinning the development of dams, however: the BOOT.

‘It is not often reported in the media but this development process is driven by the BOOT model: build-own-operate-transfer,’ says leading dam expert Professor Thayer Scudder, one of 12 commissioners on theWorld Commission on Dams and a former principal resettlement consultant for the World Bank. ‘The corporations own these dams for a period of maybe 20 to 25 years because these countries are indebted.

‘This development is driven by hydropolitics: multinationals, African governments, development banks. The rural people who need electricity do not benefit; distribution is controlled by the political elites.’

Mega-dams are justified and speeded up by structural adjustment programmes (SAPs) superimposed on underdeveloped regions courtesy of the outstanding debts contracted by venal elites such as those of Mobutu (the totalitarian former president of Zaire, now DRC). In 2006, developing countries owed debt to the tune of $2.9 trillion, servicing more than $570 billion per annum. SAPs and debt-cancellation programmes such as the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) initiative impose structurally exploitative, non-negotiable policies privatising stateowned utilities including electricity and water.

Yet even debt cancellation may sometimes be tied to corporate interests, as in the case of Ethiopia’s Gilgel Gibe III dam, currently under construction. Eight to 12 weeks after the Ethiopian government awarded a contract to Italian company Salini, Italy cancelled €367million in bilateral debt.

The contract was marked by a lack of transparency, awarded as it was without an international competitive tender exercise, breaching the procurement terms of the World Bank and African Development Bank. It is non-compliant with EU public procurement policies and also violated internal legislation governing Ethiopia’s ministry of finance and development. Italy’s own ministry of finance was still under investigation in 2008 for €220 million in loans provided for the Gibe II project.

Gibe III will generate an estimated 1,870MW, a fundamental component of Ethiopia’s 25- year national energy master plan, with 50 per cent proposed for export. Seventy per cent of the proposed $3.4 billion in loans has already been reserved for electricity generation – minus transmission line and substation costs.

‘The plan excludes from its investment requirements those costs related to “distribution, rural electrification and network reinforcement resulting from demand growth”’, according to a 2008 report by International Rivers.

The massive finance required violates the terms of the HIPC debt-cancellation initiative, however, which stipulates that loans must be directly linked to poverty-reduction. In 2007, the International Monetary Fund reported that Ethiopia was once again at risk of accruing unsustainable debt.

A drain on development

In 2008, eight hydropower dams accounted for 85-89 per cent of Ethiopia’s electricity, with five more currently under construction –Tekeze, Gibe II and III, Tana Beles and Amerti Neshe – estimated to generate a combined capacity of 3,125MW. Less than 12 per cent of Ethiopians have access to electricity. The bulk of Gibe III has been earmarked for export to neighbours such as Kenya and Sudan. China’s Gezhouba Group Corporation scooped two contracts; Italy’s Salini scooped three. Italy and China are also these projects’ main financiers, despite the refusal of Italy’s ECA to guarantee financially such socioeconomically and ecologically unsustainable projects as Gibe III.

The project itself began without a permit from the Environmental Protection Authority, which in 2008, after construction had begun, still hadn’t received its Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA). Crucially, the EIA when itappeared deliberately underestimated the number of persons that would be displaced, while marginalising the impact of the dam on the communities living downstream of Ethiopia’s Omo river, including the total elimination of flood-recession agriculture in the river and delta (the EIA proposed ‘rain-fed cultivation’ – despite the fact that this is not a climatic possibility for the region).

Livestock herding, equally fundamental for the 200,000-500,000 agropastoral peoples from eight different ethnic groups living in the area – many of them armed in the battle for resources – would also be virtually eliminated due to a lack of surface water. The Omo flows south for 500km from the site of the dam, feeding the Omo National Park, an area of tremendous biodiversity populated by 15 different tribes, all directly dependent upon the river for sustenance.

The dam will impact on three countries in its immediate wake: south-western Ethiopia,south-eastern Sudan and north-western Kenya, resulting in the destruction of theriverine stocks, woodlands, biodiversity and the sustenance of surrounding peoples via a 60 per cent reduction of river flow.

Though dams are usually packaged carbonneutral, the 20.4 million cubic metres of biomass soon to decompose in the reservoir area will generate significant greenhouse emissions. Each year, 52,000 mega-dams release 104 million metric tonnes of methane, a potent heat-trapping gas and the largest single source of human-made emissions.

Despite this, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which consists of 27 high-income nations, has armedits ECAs with financial mandates prioritising mega-dams as environmentally sustainable tools for socioeconomic development.

Undamming the future

‘There is nothing sustainable about large dams at all,’ says Professor Scudder. ‘There are millions of people in Africa that depend on the rivers for sustenance – they are the losers.

‘Dams will be built, though. Renewable energy from solar, wind, thermal energy has to be explored as the best possible solution, and they work very effectively with little adverse consequences for the people. But many of the problems can be avoided.’

Scudder cites Swaziland’s Maguga dam resettlement policy as a good example of political will on the part of the Swaziland and South African governments. Its compensation packages offer irrigation via a 23km canal,fenced grazing lands secured for resettledpeoples, the construction of public roads for farmers and producers, cane fields in place ofthe 5,000 fruit trees made inaccessible due to relocation, education and health servicesin the host area, as well as hiring all labour for the project from the pool of displaced people.

‘The solution must be multipurpose, integrating the needs of the population, such as job-creation, sustaining the river and livelihoods, access to electricity and irrigation, specifically concerning the displaced and downstream communities,’ says Scudder. ‘Other solutions include developing small tributary dams, with minimal impact on downstream communities. Obviously, they have to be strategically placed – too many and you dam up the circulatory system.’

By factoring in economies of scale, the high costs of the transmission lines required to power up the country via substations could be substituted by cheap, small, micro- and picodams such as Tungu-Kabri, which benefits 212 households in Mbuiri village. Malawi’s 80- year-old Mulanje micro-hydro system powers up the Lujeri Tea Estate (the second-largest tea producer in Malawi); it generates 600kW,enough to power a village, and has yet to require any maintenance.

The best solution lies in integrating needs with each region’s ecosystem services, such as solar power via panels, a decentralised, ‘democratised’ form of energy requiring little in the way of skills, thermal, wind and tidal.

Wind as a form of energy is being seriously considered by the Ethiopian Electric Power Corporation (EEPco), which released a reporting 2006 stating that hydro-dependency presented a tremendous obstacle in light of Ethiopia’s drought, and recommended diversification. Wind was identified as a viable source of energy for nine months each year, in contrast to water tables, which peak after June.

South Africa’s Professor Vivian Albert has developed cost-effective 60W solar panels (currently in production stage) with an estimated price tag of less than $10 per panel. Just 20 square metres of installation is capable of powering up a house with an under-roof size of 180m² and all mod cons, including fridge, stove and computers.

Unlike oil, coal, mega-dams and uranium, renewable energies constitute important democratised sources delinked from capitalintensive extractive, and government- andcorporate-controlled, industries. Commodified in the context of sustainable exploitation, these sources also ensure sustainable socioeconomic policies, recognising an Earth-centred, rights-based system.

Grammy-award-winning musician Ali Farka Touré, an ancestor of the ancient Malian empire that born of the Niger river, once told a friend of mine, author Joan Baxter: ‘Without the river spirit I would be deaf and have no voice. I would cease to be’. This truth must inform the electrification process, specifically in the context of mega-dams. Without it, Africa will be damned in the name of development.

Khadija Sharife is an investigative journalist, researcher and visiting scholar with South Africa’s Centre for Civil Society (CCS)