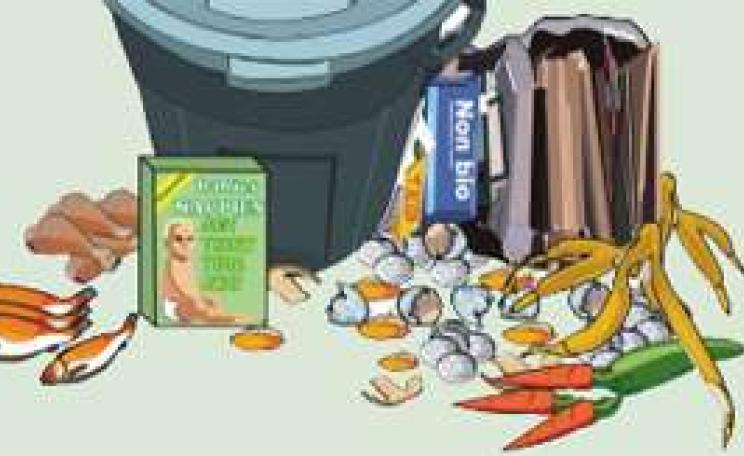

Organic waste and landfill

Contrary to instinct, organic waste actually does more harm than good in landfill. In a process called laxiviation (that is as repulsive as it sounds) organic waste gets compacted and mixed in with toxic elements such as oils, paints and detergents. Since oxygen is absent, organic materials undergo anaerobic decomposition and emit biogases such as methane and carbon dioxide that contribute to the greenhouse gas effect. Once the organic waste liquefies it seeps down into underground waters and takes all the toxic elements mentioned above along with it. This mess then hits the closest river source, potentially polluting all related water bodies, soils and living organisms, including humans.

Some waste-management companies have found ways of dealing with these problems, but only with limited success and always with huge price tags attached.

Community worms

Many cities, town councils, school canteens, restaurants and community groups are planning and piloting worm composting as an efficient means of dealing with organic waste instead of filling up landfill sites.

Large-scale vermicomposting has been practised for more than 20 years by various municipalities and industries as a cost-efficient and environmentally friendly way of reducing waste. The city of Toronto, for example, now uses a vermicomposter to treat the organic waste picked up from citizens' doorsteps. Once the organic waste has been separated from recyclable and unwanted materials, anaerobic digestion is used to produce biogas and organic material that can be made into compost. The finished compost is then used in landscaping, agriculture, soil erosion control and soil remediation projects. The worm compost is also sold to gardeners and farmers, but its benefits are poorly known, so the market for it is as yet undeveloped.

Why worm compost?

Amazingly, ‘red wigglers’ (also known as manure worms) can eat the equivalent of their weight in organic ‘waste’ every day. Once ingested the organic waste is neutralised in the worm’s gut before being excreted as a nutrient-rich, dark humus called castings. The worms work in close collaboration with many micro-organisms that decompose organic matter, the results of which get mixed in with the worms' castings and produce rich, life-giving compost. The benefits are numerous:

• a worm-composting system takes a greater range of waste, breaks waste down more rapidly and requires less maintenance than a regular composter;

• it can work all year round;

• the nutrients produced by the worms are already plant-soluble;

• the worms neutralise many toxins in the original material;

• worm compost has a more complete and generally more complex nutrient base;

• with worms, composting is a continual and rapid process, which means that there is always some compost ready and available for use in your bin.

At home

Having a worm bin is one of the few ways in which people living in cities can have a real impact on a huge environmental and economic problem – organic waste in landfill sites. By harnessing the power of the lowly worm, city dwellers can reduce their household waste output by up to 40 per cent each year, and can produce a constant supply of high-quality fertiliser for their house plants, garden, lawn or friends. And on their way toward zero waste, ‘wormers’ can feel more connected with the earth and become fascinated with their very own ecosystem. See the opposite page for instructions on setting up your own worm bin.

How good IS worm compost?

Worm compost or humus is a very powerful fertiliser for plants of all kinds. The neutral, nutrient-rich and airy compost is often called ‘black gold’ as it greatly improves soil quality and enhances plant growth, health and disease resistance. It also controls soil erosion, increases soil’s water-holding capacity, reduces water demands of plants and trees, neutralises soil toxins, fixes heavy metals and reduces mineral leaching from the soil. There is no excuse to use inorganic fertilisers and pesticides.

As if a rich compost was not enough, worm composting can also produce ‘compost tea’ for your plants. You can make it at home just by diluting the run-off liquid from your bin, or you can go professional and brew some compost with a glucose source and fungal elements to improve its effectiveness.

Home composting

In 1996 the US Composting Council analysed back-yard composting programmes and concluded that they were successful and cost-effective throughout the US, regardless of community size or socio-economic status.

The benefits include:

• lower collection, transfer and centralised processing costs;

• lower residential rubbish bills (where unit costing exists);

• new jobs through home composting programme management;

• less air and water pollution and traffic congestion;

• less need for fertilisers and pesticides; and

• reduced environmental and health damages.

The council calculated that worm composting could save $44 per ton of solid waste disposal costs. The US creates more than 230 million tons of municipal solid waste annually, which means worm composting could save it more than $10 billion a year.

WORM FACTS

// As members of the Annelid phylum, red worms have probably been around for at least 500 million years.

// It has been said that the ancient Babylonians used worm composting to create the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, one of the Seven Wonders of the World.

// Red worms were taken to North America in the 17th and 18th centuries by European travellers who carried their plants with them.

// They’ve been used for breeding and composting since the 1950s.

// Worms have no arms, legs or eyes, but they do have five hearts.

// There are approximately 2,700 kinds of earthworms.

// In one acre of land there can be more than one million earthworms.

// The largest earthworm ever found was in South Africa and measured 22 feet from its nose to its tail.

// Charles Darwin spent 39 years studying earthworms more than

100 years ago.

// Worms are cold-blooded animals.

// Worms can grow a new tail but not a new head if they are cut off.

// Even though worms don’t have eyes, they can sense light, especially at their anterior (front end). They move away from light and will become paralysed if they are exposed to light for too long (about one hour).

// If a worm’s skin dries out it will die.

// Worms are hermaphrodites, which means that each one has both

male and female organs. They mate by joining their clitella (swollen area near the end of a mature worm) and exchanging sperm. Then, each worm forms an egg capsule in its clitellum.

Websites to visit for more information:

DIY worm composting

It's easy, cheap, fascinating and can be done outside or inside all year long.

Even if you live in a tiny flat, all you need to start worm composting is:

A bin – Build your own from wood or purchase a worm composting bin (many are offered on the web). As for size, each square foot of surface area will process a pound of food. (Example: a 2' x 3' x 12" worm box will accommodate waste generated by a family of two.)

A bed – Put about two inches worth of hand-shredded newspaper in your bin. You can also add crumpled dry leaves, shredded cardboard (the glue makes the worms horny) or wood chips. Then add some water to the bedding until it's damp like a wrung-out sponge. It should be loose so as to allow the passage of air while shielding the worms from the light, neutralising potential odours and keeping pests away.

Worms! – Get some from other avid wormers who have just harvested their bin and want to share. You can also buy them on many websites and stores that sell them for fishing. Make sure they're red wigglers and not earthworms (which are slow and uglier; it’s a worm thing). A pound should be fine to start.

A nice home – Worms like to be in a stable environment, at temperatures between 32° and 84° Fahrenheit. If you notice they're not squirming much, move them to a warmer place. Experiment with different locations until you find the right one.

Food – All things organic. Add fruit and vegetable scraps, tea leaves, coffee grounds (they make the worms peppy), crumbled eggshells, grass cuttings, ashes and nasty gooey things at the bottom

For ethical and sustainable suppliers of Home and Garden goods and services check out the Ecologist Green Directory here