One per cent of the surface area of the world's deserts would be enough to meet our current electricity needs

The logic of the idea would seem obvious to a child: the human race needs to wean itself off fossil fuels, so why don't we build solar power plants in the world's deserts, to give us all the energy we need?

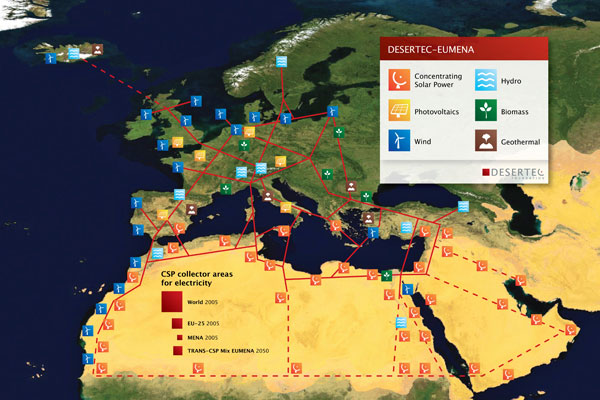

This concept has long been promoted by Desertec, a European network of scientists and engineers, which argues that just 1 per cent of the surface area of the world's deserts could generate as much electricity as the world is now using.

What do you think? Comment here

Desert solar power

Desertec envisages a massive deployment of solar technology in Middle Eastern and North African countries, exporting electricity to Europe. The vision may seem idealistic, but there have been signs recently that politicians and industry are starting to take the Desertec proposals seriously.

A recent Desertec seminar at the House of Commons was attended by the energy minister Lord Philip Hunt, as well as the Conservative shadow energy minister Charles Hendry and the Liberal Democrat shadow secretary of state for energy and climate change, Simon Hughes.

All three professed support for the concept, with Lord Hunt declaring, 'I am very interested in the work that you are doing.' Just words? Maybe. But Hunt promised that the Desertec will be seriously considered by the European Commission as it tries to make plans for future supplies of renewable energy for the whole region.

Taken seriously

The European Union is aiming to provide 20 per cent of its energy from renewable sources by 2020, and a much higher percentage by 2050. With this in mind, the European Commission has begun drafting the Strategic Energy Technology Plan, which will attempt to explain how renewable technologies can be made mature enough to supply a large part of Europe's total energy needs by 2050.

The SET Plan, as its known, is still in its early stages, but Desertec is part of the deliberations. Gus Schellekens, a director in the sustainability and climate change team at business advisors PriceWaterhouseCoopers, sees the SET Plan as a tentative first step towards the kind of European unity needed to make Desertec a reality.

The Desertec project would involve power lines being stretched across the desert and Mediterranean sea

Supergrid

A key part of the Desertec vision is for a 'supergrid' that can distribute renewable energy across Europe, be it hydro power from Scandinavia, wind power from the UK or solar energy from the Mediterranean states and North Africa.

In addition to building this supergrid, the European states would probably also have to agree a system of subsidies to make solar electricity imported from North Africa commercially viable.

'The SET Plan has the potential to be what's needed,' says Schellekens.

Next month he will publish his own report on the future of renewable power in Europe and North Africa, which argues that unified political support for Desertec across Europe is essential before investors will risk their cash to fund the building of solar power plants in North Africa.

'Unless you have the right signals coming from government level, you don't have what the market needs, nobody moves and no-one does anything,' says Schellekens.

Price barrier

The sheer cost of solar power is another obstacle.

Electricity produced by even the cheapest solar technology still works out at $160 per megawatt hour (MWh), compared with just $60 per MWh for electricity produced by coal-fired power stations and $80 per MWh for the most efficient gas-fired power stations, according to Jenny Chase, senior solar analyst at Bloomberg New Energy Finance, which analyses investments in renewable energy.

Chase acknowledges that government subsidies in Spain and Germany have already helped bring down the cost of solar power dramatically, but she finds the Desertec concept unconvincing.

'The idea is to generate an expensive form of power and then transport it across long distances. That doesn't stack up without significant amounts of subsidy. I don't know if that will come, but I suspect that given the timescales involved, solar power may become cheap enough to deploy widely in Europe without needing to transport it from north Africa,' she says.

African solar industry

North African governments are taking steps to build their own solar industry.

The seminar at the House of Commons included a presentation from the Morroccan energy minister, Amina Benkhadra, who is seeking $9bn of investment to build 2000 megawatts of solar capacity in Morocco by 2019.

Tunisia has launched a similar scheme, the Plan Solaire, and Schellekens expects further solar plans will soon be launched by other North African countries. For the moment, he doubts there is much enthusiasm among investors:

'We are at a point in the [economic] cycle where lots of money has been lost and what is left is being looked after carefully.'

The private sector has also begun to investigate Desertec. Last July in Munich, 12 energy and financial companies including Deutsche Bank and E.On agreed to finance a three-year feasibility study, known as the Desertec Industrial Initiative.

The group has been convened by Munich Re, the world's largest reinsurance group, which believes solar power in North Africa could deliver 15 per cent of Europe's electricity by 2050.

Concentrating solar power

Desertec supporters say the technology needed to carry out the plan already exists. It advocates the use of concentrating solar power, whereby mirrors are used to concentrate sunlight into small areas to generate heat. This heat is used to generate steam, which in turn drives turbines to generate electricity, just like a conventional power station.

The advantage over conventional solar panels is that it does not need expensive silicon. It does, however, need lots of direct sunlight, which makes it ideal for deserts but less suitable for most European countries.

Another advantage is that generation can continue at night, using spare heat that has been stored in tanks containing melted salts or in concrete blocks. Six concentrated solar power plants are already up and running in Spain and several more are under construction.

Lord Philip Hunt warns, however, that the technology will need to prove itself on a large scale - running at hundreds of megawatts rather than demonstration-scale plants producing merely tens of megawatts - before Desertec can take off. He also pointed to the massive scale of investment that would be needed, most of which will have to come from the private sector, plus the importance of creating the right regulation across Europe, 'which will not be easy'.

Encouragingly, Hunt concluded, 'none of these challenges is insurmountable'.

Useful links

Desertec Foundation

| READ MORE... | |

|

COMMENT Solar lighting spells the end of kerosene in Africa A simple but effective solar kit is helping to bring light to homes in the less-industrialised world without the choking side-effects of kerosene lamps |

|

HOW TO MAKE A DIFFERENCE India's plan for a solar power revolution India is set to embark on the country's largest solar endeavour - increasing solar capacity from 3 megawatts to 20 gigawatts by 2020 |

|

NEWS Under the hood of the solar electric car Cambridge University's solar electric car 'Endeavour' was unveiled in July as a contender in the Global Green Challenge - a gruelling race across the Australian outback in October. |

|

HOW TO MAKE A DIFFERENCE PHOTO GALLERY: Visionary architect unveils eco designs An exhibition in Beijing reveals architect Paolo Soleri's latest radical green city concept |

|

NEWS ANALYSIS Local electricity: Africa goes off-grid Giant wind farms may grab the headlines but plans to develop local off-grid electricity will have bigger impact on Africans and carbon emissions |